According to a study by Group RATP, on average, a trip by public transport in Ile-de-France takes 43 minutes. Walking, changes and waiting account for 18 minutes of this time and the rest of 25 minutes is dedicated directly to being in transport or 24 minutes for those who only take train or metro.

For a century, the ways to spend time on the metro stayed the same: reading, chatting with fellow travelers or sleeping were almost the only options available. This has started to change recently when the quest for connected transport reached the underground world. And Paris metro kept well with trends. Testing of Wi-Fi on the stations was launched in 2012 and 15 stations offer now to surf on Internet while waiting for a train. However, the major jump into the universe of connected metro is now underway with the development of 3G/4G connection, which is part of the strategy Métro2030 introduced by RATP. Line 1 is mostly covered with the high-speed connection and, by the end of 2018, the expected number of stations covered is 120, while by the end of 2019, RATP promises full coverage (not clear if this means the connection in the tunnels or only at the stations though).

There is no doubt that, taking into consideration the difficulties of granting access to internet to the underground travelers, what RATP and most metro operators around the world propose is quite a good deal. But is it possible to step even further and organize the flawless Wi-Fi connection in the trains moving through the metro tunnels? Can this become a profitable venture? How to monetize such a massive project? The answers can be found by looking at the examples that already exist. The pioneer in deploying free Wi-Fi in metro tunnels was Moscow. Developed in 2013, the deployment was finished by 2014 and all metro lines became connected. MaximaTelecom, the company that developed the project, does not disclose the information on investors but claims that all the involved capital is private. This same company repeated the project in Saint-Petersburg in 2017. The idea is slowly taken up by other players around the world – Toronto metro operator promises tunnel network coverage by the end of 2018. Shall other cities follow? Looking closely on the Moscow project might give insight into this.

Moscow – was the experiment successful?

Technological challenge

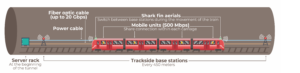

Prize-winner of Wi-Fi Industry Awards 2015 (Best Wi-Fi Deployment in a City or Public Area), the project of Wi-Fi deployment in Moscow metro was not an easy venture. It included equipping 5450 train carriages with Cisco equipment, laying 880 km of fiber optic cables in the tunnels during nights at the depth of up to 84 meters (the depth of the deepest station – Park Pobedy) and developing broadband solutions adapted to the peculiarities of the project (conducted by RADWIN). It was decided to step away from the traditionally used in tunnel environments system of leaky feeders (or radiating cables), which are used, for example, to provide access to 3G in metro tunnels, and to develop a brand-new system for bringing Wi-Fi underground. The system functions as follows:

Every 450 meters in the tunnel there are base stations connected by a fiber optic cable. Shark fin aerials installed on the first and the last carriage of the train switch between these base stations while the train is moving. Shark fin aerials are connected by a cable, which also connects mobile units installed in each carriage. These mobile units, in turn, provide Wi-Fi connection. The first and the last carriages create their own network, in order to avoid resetting the system should every time carriages are detached from or attached to the train.

Initially, the connection’s speed achieved up to 100Mbps, while the fiber optic cable capacity was equal to 10Gbps. However, later the cable capacity was increased to 20Gbps and the connection speed increased to 500Mbps, which set a new benchmark in the industry. Tests for reaching the speed of 1Gbps are underway.

In order to ensure the fast deployment of the network (which was supposed to take 18 months) without interrupting the normal functioning of the metro, all the works were carried out at night. During every night shift, the workers laid 2 to 3 kilometers of cable. Mobile units installation in the trains was, however, more complicated as numerous types of trains were in use, including rather old ones. Each type required adjustments of the system.

Is there demand?

The short answer is yes. A lot. The number of estimated unique users is 2,5 million people per day or 40% of the 6,5 million army of daily passengers. Metro passengers generated 37000Tb of Wi-Fi traffic in 2017 or 15Mb of traffic per 1 metro passenger. In 2015, in ‘Main projects in Moscow’ vote, users granted victory to Moscow’s metro Wi-Fi. It gained 37% of votes, far ahead of its competitors.

The longer answer is not as evident as the project from time to time causes indignation of its users:

- At the very beginning, the main issue was unstable quality of connection and incredibly low speed during rush hours. This gave way to angry tweets and complaints, like: ‘How the metro Wi-Fi works: advertisement videos work, the rest of the Internet – not (sent via 3G)’. Eventually, the problem was fixed by increasing the cable throughput, and the number of complaints went down.

- New complaints emerged soon, this time because of the introduction of the obligatory authentication where first-time users had to confirm their mobile phone number. The company tried to soothe users by saying that it only complied with the changing Russian legislation limiting the anonymous access to public Wi-Fi.

- Next point of conflict, though it only impacted paid users, appeared in 2017, when the company increased by one third the prices for ‘no-ad’ subscription plans. There was no announcement and most users only found out the prices went up when they tried to extend their subscription. This time, the company’s representatives tried bringing down the users’ discontent by connecting the surge in prices to the desire to limit the popularity of the paid subscription.

- The latest splash of anger in April 2018 was caused by the news that passengers’ personal data (around 13 million users) was exposed. Due to major vulnerability, it was possible to get information on the passenger’s phone number, approximate age, gender, marital status, income level as well as on the stations the person lives and works. The issue was rapidly solved after the news went public.

In brief, the company faced the problems typical of a technological company. The arguably fast reaction to these problems, but also the fact of being a monopolist in the underground free Internet kingdom allowed it to keep the users loyal. But does this bring money?

Business model – pay or watch ads

According to Cisco, the equipment’s supplier of the project, the overall investment in the project reached $70M. The company does not disclose information on where the money came from, but claims that only private funds were used. Company managers name 6-7 years as the time necessary to break even. In this case, MaximaTelecom will see the first profits in 2020-2021. As for now, the net losses are estimated at around €5M in 2016, though this data is not official as the company prefers not to disclose its financial results.

The business model is simple. The company earns money from 2 different sources: advertisement in its network (branding of the authorization page, videos played during authorization, ads on a specially created news portal) and sales of paid ‘no-ad’ subscriptions.

Advertisement business seems to be a cash cow for the company. Around 500 advertisement space buyers can choose between various advertisement options, but also have numerous targeting opportunities: MaximaTelecom collects users’ unique MAC-addresses (MAC-address – a unique identifier assigned to a network interface controller) and analyses the behavior model to provide more relevant ads. The advertisers can create their own ad targeting cocktails by choosing among geotargeting, demographical, interests, income, device type, OS targeting, even targeting adapted to weather or time of the day. Unofficial sources claim that in 2016, the company revenues from advertisement reached around €27M.

As for paid subscriptions, the option is popular with 150 thousand active subscriptions (around half of them are used regularly).

As for competition, the company is monopolist giving full access to Wi-Fi networks in the metro, but mobile operators are not ready to surrender and are developing 3G/4G options for metro passengers. However, the mobile network connection stays unstable and limited, and it is not clear if even in a couple of years passengers will get access to high speed mobile network in tunnels.

Paris – go beyond connected ?

Can Moscow’s experience be useful for Paris? How feasible is the project in the metro that is 35 years older than its Moscow colleague?

The demand side is contradictory. On the one hand, number of passengers of Paris metro is one third lower than in Moscow. The average ride duration is almost twice shorter. Also, 3G/4G network’s deployment is underway, which might also limit the number of potential Wi-Fi users. On the other hand, these particularities did not prevent MaximaTelecom from launching the same project in the metro of Saint-Petersburg, which has 3 times less passengers than Moscow and where the rides are considerably shorter. And the fact that all the metro stations of the Northern capital are equipped with 3G/4G did not discourage the company. Despite the lower expected number of users, the project is expected to break even 7-8 years after its launch.

Project’s costs require an in-depth study. On the ‘go’ side – it is clear that there is no need to create a technology from scratch, the length of the network that is one third lower and, thus requires less equipment. These features, for example, allowed reducing considerably the costs of bringing the technology to Saint-Petersburg – from $70M in Moscow to $17M up north. The same effect can potentially be achieved in Paris. What’s more, stations are not as deep, which potentially simplifies the installation of the equipment. And not to forget the difference in income levels and market prices – in France, both advertising space buyers and passengers will be ready to pay more to get their ads to the screens of passengers for the former and to get ads from their screens for the latter, while the equipment price stays the same. On the ‘no-go’ side – additional costs are necessary to provide better security, the fact that Paris metro is older, which might require adaptation of the system to its peculiarities, as well as speculations on the introduction of 5G, which would provide speeds much higher than those of Wi-Fi connection and would ‘kill’ public Wi-Fi. This, however, is not clear yet and it is likely that, shall the Wi-Fi project be deployed in Paris, it would break even before this becomes a reality.

The outcome is not evident, especially taking into consideration the fact that MaximaTelecom does not disclose its financial data. This makes it difficult to evaluate the potential profitability of the project. But deployment of free Wi-Fi in Paris’ underground seems to be a feasible venture that might make Paris metro even more connected than it is getting now. And Moscow experience is useful to avoid the mistakes made during this pioneer project.